Inspiration from the East

In 1852, two hundred years after Japan’s Tokugawa dynasty had banned contact with the West, Commodore Matthew Perry led his American fleet to that country to “encourage” foreign trade. Previously, only the Dutch had been allowed to maintain a small trading post. Soon after a treaty was signed, goods were shipping to capitals in the West, the first “evidence” being a collection of woodblock prints by Katsushika Hokusai, in Paris.

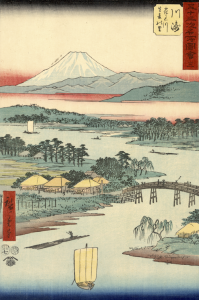

Hokusai was one of the most important Japanese artists of his day. Whistler first saw his prints and those by artist Andō Hiroshige at the atelier of his Paris printer, Auguste Delâtre. As did several of his friends in the “Impressionist” circle, Whistler developed an interest in Asian decorative arts. Two shops on the rue de Rivoli specialized in Japanese prints, costumes, circular fans, folding screens, and porcelains, which Whistler collected.

Whistler had moved to London by 1860. Two years later, the “International Exhibition of 1862” formally introduced Japanese art to the British public. More than one thousand Japanese objects made with wood, lacquer, straw, paper, metal, textiles and ceramic, as well as two hundred wood block prints, were presented. Whistler frequented the International Exhibition, making purchases of “Japonisme” at the nearby “gift shop,” (now Liberty of London). He was among the first, and most enthusiastic, customers for those items, and one of the first to introduce Japanese art and artifacts to Britain.

“This artistic abode of my son” wrote his mother, “is ornamented by a very rare collection of Japanese and Chinese, he considers the paintings upon them the finest specimens of Art… some of the pieces are more than two centuries old.” Whistler “got up” the rooms in his house “with many delightful ‘Japanesisms,’ which included a pagoda cabinet, and purple Japanese fans which were tacked on the wall and ceiling. He ate on blue and white china, and slept in a Chinese bed.

“Look at how the Japanese understand it. The same colour reappearing continually like the same thread – the whole forming an harmonious pattern.”

– James McNeill Whistler

In 1863, Whistler began placing objects from his collection in his paintings. He dressed Western models in kimono, set them in an interior space, and surrounded them with Japanese folding screens, porcelains, lacquerware, parasols, prints and fans.

“Variations in Flesh Colour and Green: The Balcony,” Oil on wood panel, 1864-70. Courtesy of the Freer Gallery of Art, Gift of Charles Lang Freer

One of these “costume pictures,” called Variations in Flesh Colour and Green: The Balcony, differed in setting from the others. Whistler placed his models outside, on the balcony of his studio overlooking the Thames. The view incorporated the smokestacks and piles of coal that dominated the far side of the Thames, the area called Battersea.

The Balcony developed over the course of four tumultuous years, during which time Whistler recognized that he had paid scant attention to his studies in Paris and would need to re-educate himself. He would have to move away from the influence of Gustave Courbet’s Realism and develop a style and a subject of his own. In The Balcony, Whistler discovered that subject, the urban landscape, and hinted at the direction that would come.

Whistler’s developing style owed much to the influence of Japonisme. By the early 1870s, he had studied the principles of composition, the approach to color, and the simplicity of design that could be found in Japanese prints and porcelains. These discoveries would result in his best-known works: the painting of his mother, and the form called the “Nocturne.”